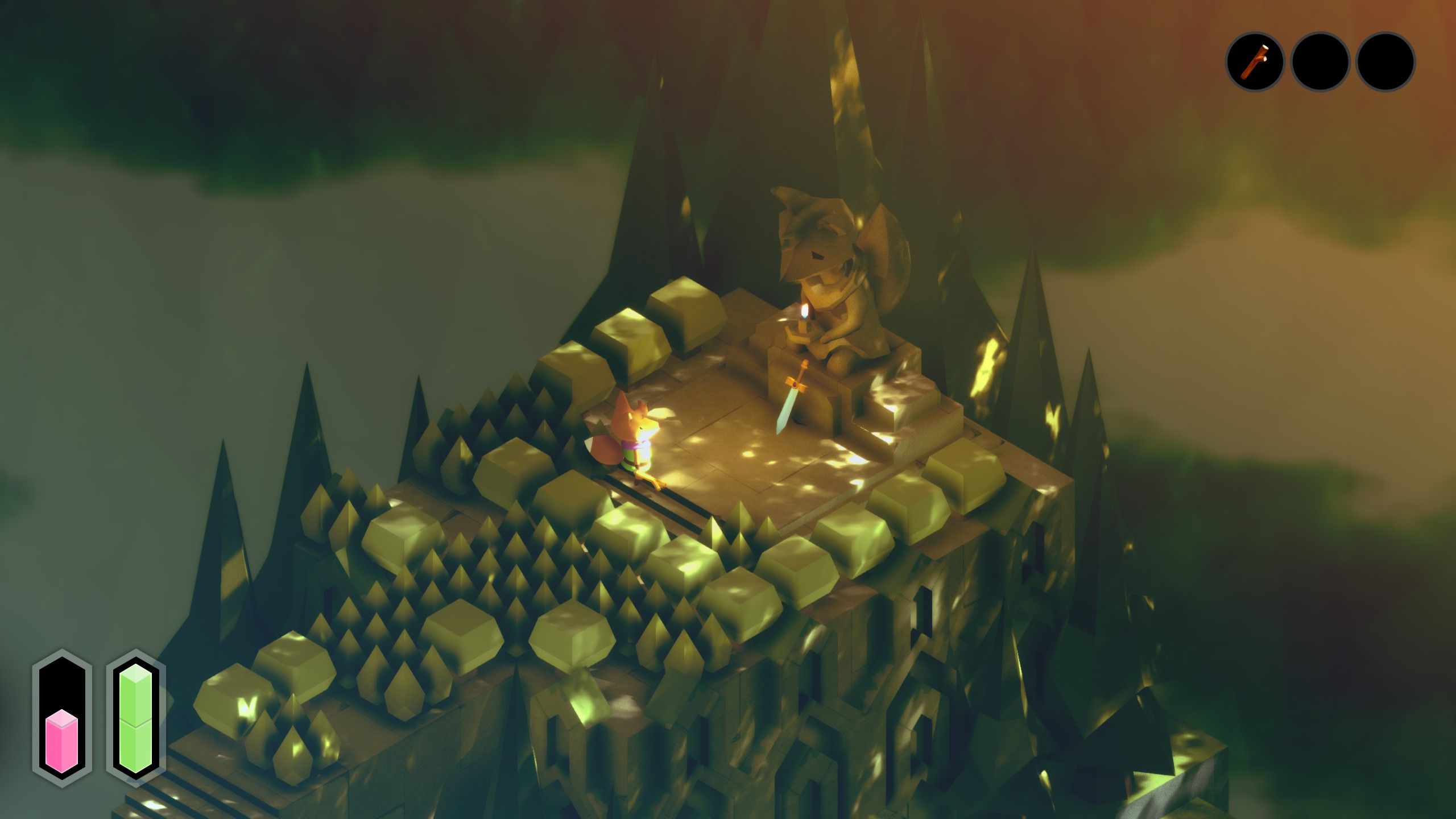

You just need to look at it to understand. The greenery, the shrubs, the iconography, it’s all immediately and intentionally evocative of Zelda in a way that the other recent isometric slicer-dicer, Death’s Door, was a little more demure about. While Death’s Door coated over its emerald influences with a coat of corvid black, Tunic, even in its name, acknowledges the debt. It is literally cutting its cloth from Link’s shirt.

The world has a papercraft feel, constructed of sharp-edged ramps and boxy buttes. Telescopes dotted around will give you a more zoomed-out view of nearby areas, letting you get a sense for what kind of enemies are coming up. At first you deal with these slimes and shadowy knights by hitting them with a stick. Then you find a sword, a shield. Later still, bombs, a magic staff, an ice-blasting dagger.

This is not always for betterment of butchery. Getting that sword from the East Forest means you can now slice bushes that once got in your way. Finding a lantern lets you light up that dim tomb you stumbled across. So far, so familiar. A tried-and-true broadening of the world through weapons and tools, made satisfying by some classic foreshadowing. A conspicuous stone door, a curious tuning fork sticking out of the ground.

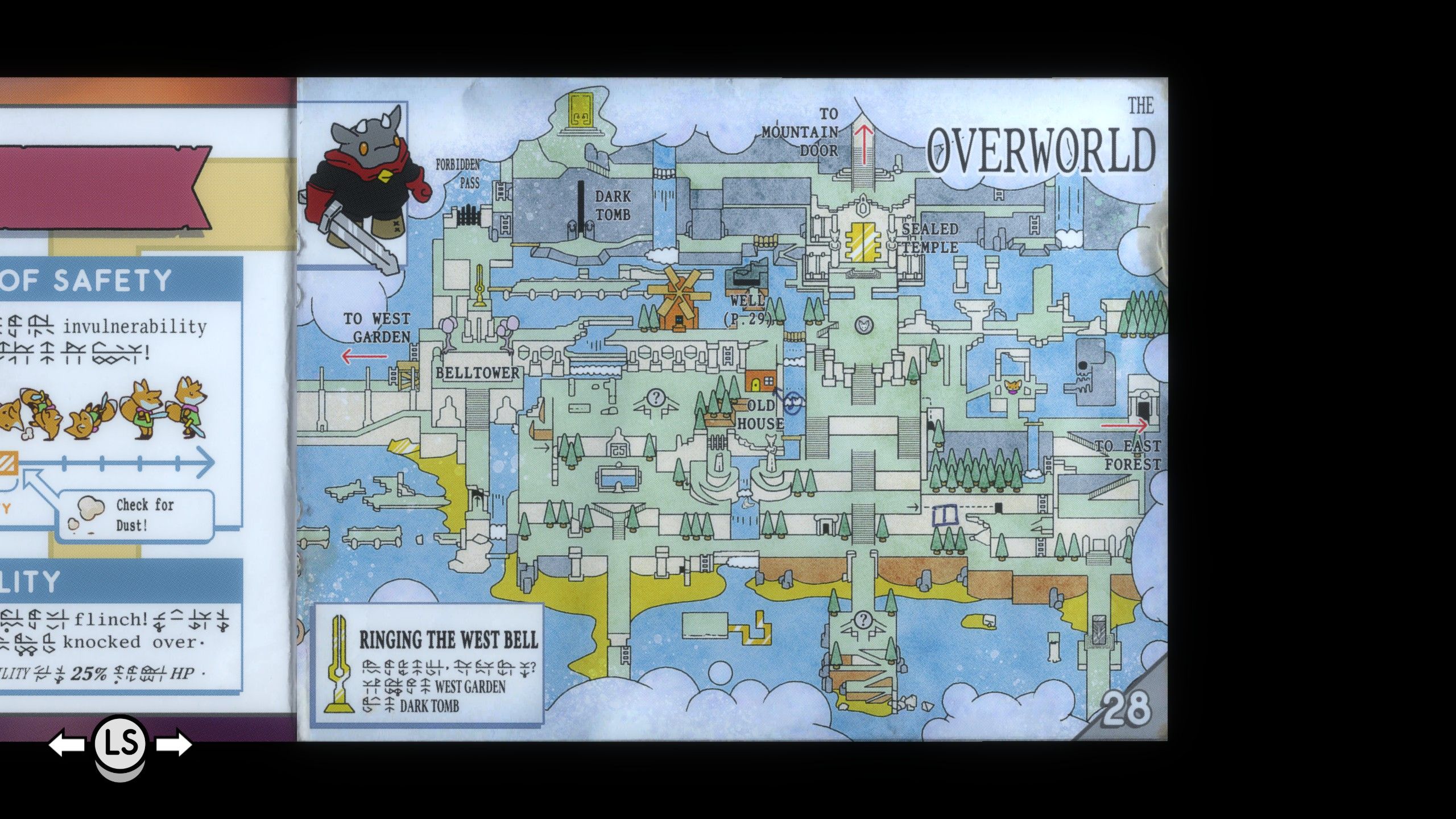

But that world-opening is also done in another, more novel way. Throughout the kingdom you find scraps of the game’s manual. These are neatly illustrated pages, covered in an unknown language of runic symbols, with only a few key words in English. As the manual comes together, you come to see Tunic not just as a tribute to SNES-era games like Link To The Past, but also a tribute to the paraphernalia of childhood videogamesing. Manuals, game guides, messy notes. It is lovingly realised. You can practically smell this instruction booklet.

More practically, it adds a sense of discovery to the finer details about enemies and environmental obstacles. Exclamation points and diagrams show you that some objects are related, while capitalised words in English run alongside fuller descriptions entirely in Tunic-ese. “HOLY CROSS,” says one, next to a silhouetted picture and inscrutable text. It raises questions at regular intervals. What’s so special about these gold coins, or these flowers? These shrines and golden platforms have some connection - but what? Some pages have scribbles in ballpoint pen atop the instructions. It’s an artificial yet playful way of eliciting the emotions of a child delving into a strange 16-bit realm for the first time. And it allows for sweet moments of revelation in which you discover a new page, only to realise you had a necessary power all along.

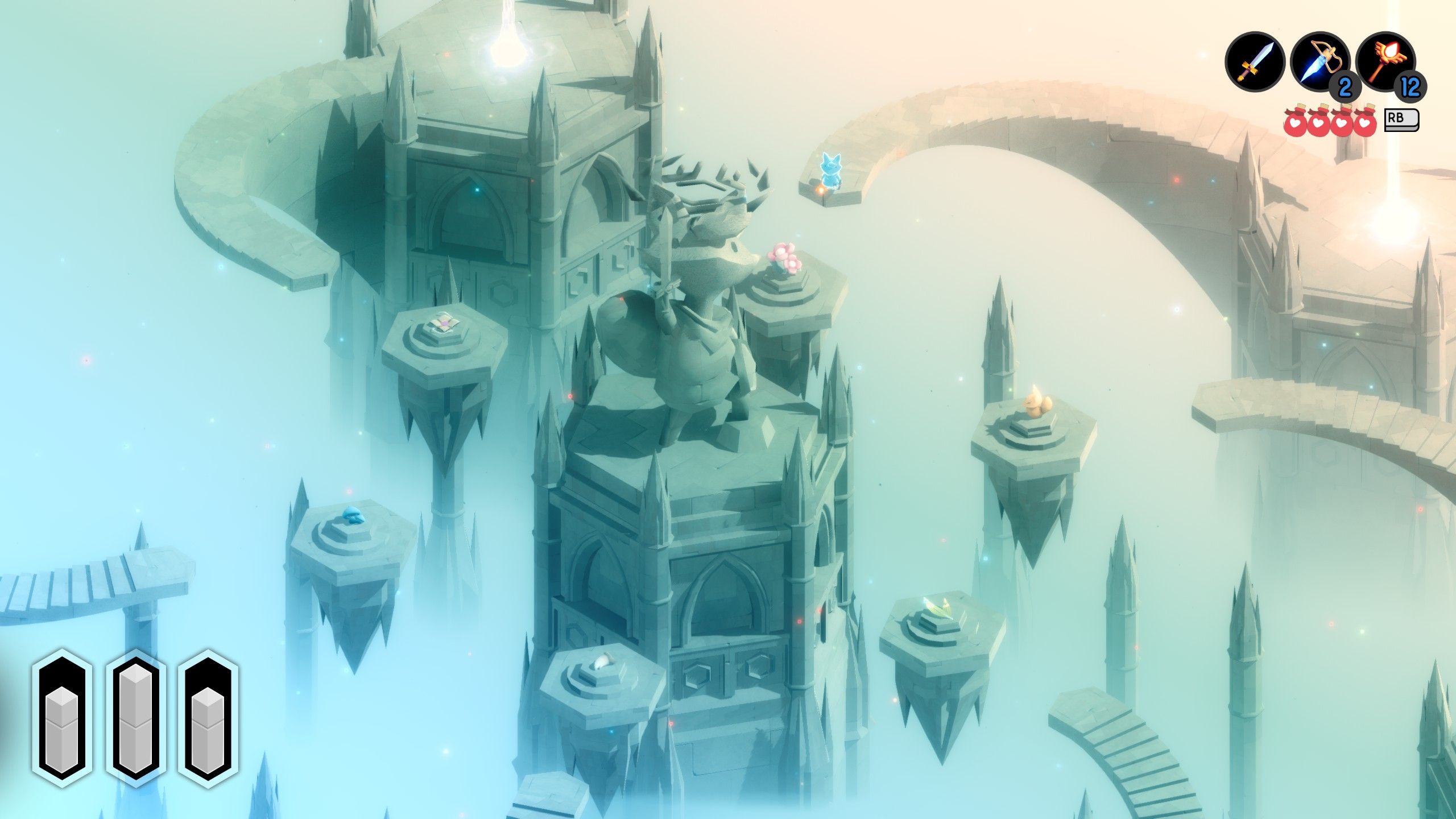

Exploration is king. There are tons of treasure chests and covert passageways, not just hidden behind trees or tucked away in caves, but also obscured by the traditional black void of videogames, the isometric view acting as a kind of gatekeeper of secrets throughout the game. There are labyrinths of invisible walls and, yes, secluded paths veiled by waterfalls, and plentiful shortcuts kept out of sight thanks to quirks of perspective. An absolute joy to me, the shortcut liker.

A more cautious designer would be reluctant to overuse such line-of-sight chicanery. They would make hidden spots clearer or give the player control of the camera, letting them spin the perspective themselves. Not here. Tunic holds fast to its 90s design language, the idea that your camera is as much a jester as it is a guide. And the jester is not under your command. It works, provided you’re equipped to read such cues. A dark corner into which I cannot see because of an overhanging block? Well, I shall walk around in there and feel it out until I’m satisfied it’s a dead end.

Some might find that sightless groping for hidden goodies tiresome. Especially in those moments when you move between areas, whereupon the dull silhouette of your Fox hero gets washed away in the world’s hues (colourblind folk, be warned). But it does give Tunic that sense of depth you sometimes get with clever fixed-perspective games. Not only literal depth, but flouncy metaphorical depth. The axonometric point-of-view starts as a visual design decision, and in its repeated use, becomes a theme. When you look closer, even Tunic’s mysterious hieroglyphs are constructed out of the edges and vertices of a stretched box.

That fictional language is meaningful (I figured out the word for “you” and the cardinal directions) but it is not explicitly translated by any in-game system, a la Heaven’s Vault. This is emblematic of Tunic’s old-school attitude. It trusts you to figure this stuff out. That’ll make linguist fans of the Hylian language happy. But it extends to blow-by-blow exploration and combat. Hours after I got bored of cutting stray blades of chunky grass, I discovered they could be set on fire, and the fire would spread so long as there were neighbouring clumps of grass. “Oh wow,” I said, as I burned to death.

When you die, you get blooped back to the most recent shrine you rested at, and it does the Souls thing of leaving some dropped coin behind in ghostly form for you to recover once you make your way back. It’s only a small chunk of currency, nothing so punitive as your entire wallet, and there’s a nice shockwave effect when you pick up your phantom cash, knocking back enemies and giving you some breathing room.

Playing this side-by-side with Elden Ring has only strengthened an observation already made by many others, that Soulsbornes are simply Zelda for people who like to bleed. Tunic pays less homage to bonfires and beefiness than, say, Death’s Door (not to pit this fox and crow against one another too much, I’m not bloody Aesop). But it does nod to Souls from time to time in its checkpoint shrines, its health flasks and in other more cursed moments.

Yet Zelda is where the fox’s heart belongs. For better and sometimes for worse. That 16-bit pact of player trust also means I got completely lost in the exact way I often did when playing Link To The Past as a youngster, wandering the length and breadth of the overworld, trying to figure out what small doorway I’d missed, what tool I was supposed to unlock next. Do I need something that lets me use these hooks to cross gaps? Or is it the (probably explosive) ability to get through these strong stone doors?

This is the flipside of the hands-off approach. Sometimes the manual’s cryptic hints will lead you toward the correct place. And sometimes you will roam in wide, circular arcs between different areas, wondering what the game wants from you. I lost two hours revisiting previous areas looking for that grappling ability because the mouth of the only dungeon left known to me was out of reach and it boasted a big hook next to it. “Ah, a big frog-shaped rock with a clearly posted ability requirement,” I thought. “That’ll be the entrance.”

Foolish. The actual entrance was hidden by two turns of the screen behind some pillars and up an unseeable ladder. The same isometric tricks that bestow pleasing moments of discovery can also cause frustrating critical misses. Don’t worry. I got the grappling hook. It was inside the dungeon.

I can forgive moments like this, mostly because Google (and our own Tunic walkthrough guide) can prevent these problems for you in a way it cannot for me, because the game isn’t out yet (hark, the reviewer’s curse). But there are those who won’t always enjoy the spectre of SNES cluelessness that Tunic conjures up.

The difficulty of the fighting also hits an abrupt ramp at some of the boss battles. Compared with the exploratory rhythm of the rest of the game, the tough boss fights felt out of step. Tunic’s aiming system can be temperamental, sometimes losing track of targets or refusing to lock on after being hit. In normal brawls it’s tolerable, but in boss battles with minions or other targetable objects it becomes a pain to manage what you’re aiming at.

One boss battle was so hulking and jumpy that he seemed to demand the use of multiple tools with timed darts behind cover. Really, he simply required brute force and luck. If there’s one thing from Souls I wish Tunic had left behind, it’s the toughness of these bruisers compared to the rest of the game’s combat. (Oh, and the lack of any pause or slowdown when bringing up your inventory. Panicking through items to swap out a firepot while the enemy charges at you in a Soulslike? Yes. Doing the same thing in Zeldalike? No thanks.)

These grumbles aside, Tunic is a resolute and intelligently made adventure in its own right. Modern reimaginings of the “classics” often reproduce mechanics of old games in cleaner ways but without understanding the game’s design from a holistic level. Nostalgic platformers give you coyote time, but then fill their world with needless dialogue. Retro shooters throw hordes of enemies at you, but fail to construct smart spaces in which to fight them. If this plucky fox ’em up flatters-by-imitation too much, it is only because it has examined its reference in its entirety. Like an overhanging camera view, Tunic sees Zelda from the top to the bottom. It is a tribute well-paid.