I would have said that about The Suicide Of Rachel Foster too, at least based on the bulk of the game. It’s a decent enough first person explorey mystery along the lines of Firewatch or Gone Home, but, you know, not as good as either of those. Then, in the last half hour or so, it goes properly off the rails and the content warning is proven necessary. Not in a good way.

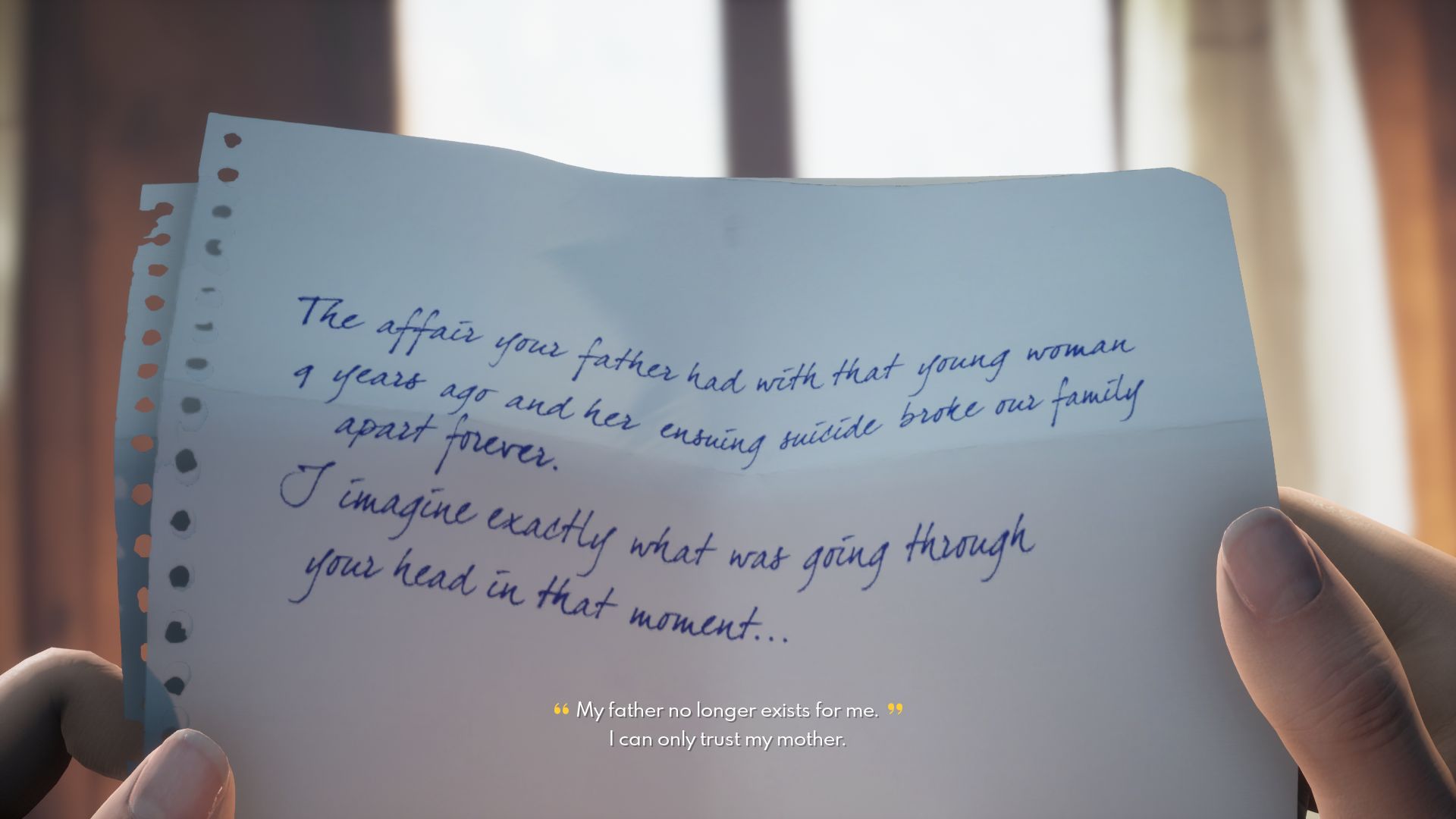

It’s 1993. You play as Nicole, a grown woman now returning to the Timberline, an old mountain hotel that belonged to her parents, Claire and Leonard. They ran the hotel and lived there with the teenaged Nicole, while Leonard was tutoring local girl Rachel Foster, and by all accounts it was a pretty successful set up. Until. Ten years before the events of the game, Nicole and her mother left suddenly, and never returned, after it was discovered that Leonard was having an affair with the 16-year-old Rachel. Shortly thereafter Rachel went missing, and was found a few days later at the bottom of a cliff, with a note indicating she had taken her own life. It seems she probably died on the same day that Claire and Nicole left. So far, so titular - and obviously, there turns out to have been something fishy about Rachel’s death. Nicole, back at the Timberline to inventorise and sell it after the deaths of both her parents, ends up investigating this piscine odour - this whiff of trout - while she’s trapped there for a few days during a snowstorm. She’s not entirely isolated, however, as she has an early mobile phone that lets her speak to Irving, a FEMA agent stationed nearby. Irving is unreasonably invested in Nicole’s plight, for reasons you eventually discover.

Look, you know me. I’ll forgive a lot for a mystery where I noodle around an empty building full of sweet, sweet environmental storytelling. The Suicide Of Rachel Foster is actually really good at that, too. The apartment where Nicole’s dad lived out his mouldering last days in a likewise mouldering hotel, for example, is full of books about physics, the stars, and space. But around his bed you find tomes about ghosts, and how to talk to the dead. Leonard’s thinking had, we can infer, changed over the last decade. And there isn’t a voiceover telling us that - it’s just something to look at and understand. That’s cool! Not entirely cool enough, though. Where Gone Home lead you naturally through the empty house as you discovered new things, The Suicide Of Rachel Foster leads you by the nose, partly because, though the Timberline is a nice vision of gently spoiling grandeur - the Miss Havisham’s wedding cake of hotels, but with a bit of The Shining flavour - it’s a lot bigger than a house. Gone Home works because you know how to navigate a family home. The Timberline doesn’t, because you don’t feel at home in a hotel by definition, even if Nicole does. You, as a player, are one step removed from the uncanniness when creepy things start to happen.

There are isolated pockets in the building where you busy yourself most often - the apartment, the offices, the basement - but in between are corridors of empty rooms that you can’t enter, which might as well be blank space. Similarly, you find tools that have a specific purpose (a Polaroid camera that you use when the lights go out, or a parabolic mic to track spooky noises) but each is only used once, in one set piece, and so they end up feeling spare. Worse is the actual storytelling. The voice actors do a good job of making Nicole and Irving interesting, the former a kind of a caricature of a strong independent bitch who needs no help from nobody (who can blame her?), and the latter a kind of extremely nice nervous dork, the sort of person I’d describe as a wetty. But the pacing of the central mystery is all wrong. Rather than teasing it out, getting a sense of the shape of it, and gradually uncovering more facts, Nicole is spooked out for a few hours, before the actual reveal is dropped all at once in a sticky rush, like so much gunge poured on hapless parents by Dave Benson Phillips.

The most glaring problem is how The Suicide Of Rachel Foster fails to meaningfully engage with its central themes. Leonard’s chief sin is that he cheated on his wife, and not that he started shagging a 16 year old who he was teaching, for God’s sake. Rachel is not framed as a probable abuse victim, a child who became pregnant by her father’s best friend (!), but as a tragic young woman - a star crossed lover, almost. One could tenuously argue that this is because of the point of view that we see the events from, and that the game is clearly aware of how creepy the situation was. Nicole has a dream in which she hears her father asking if she knows how much he loves her. “Tell me again, daddy,” she says. “I love you… Rachel,” he replies, at which point I involuntarily made a BLEH face and looked away from the screen. But after that, there’s no tussling with the implications of Leonard’s actions; rather, the characters consider Rachel’s situation in the light of Claire and Nicole herself being jealous. I know moments ago I was praising the environmental storytelling not telling me what to think, but in this case both Irving and Nicole end up very defensive about Leonard and Rachel’s relationship, and I could have done with at least one person leading a coalition for reason. The denouement of the whole thing is a weird clanger of epic proportions, and I’m going to spoil it here. So if you were planning to play The Suicide Of Rachel Foster, then here the review stops for you.

At the end of the game, Nicole finds herself alone, it being revealed that Claire battered Rachel to death with a hockey stick out of the aforementioned jealousy. Events now suggest that, in fact, both Leonard and Claire eventually took their own lives. Irving has walked out into the snow for extremely unlikely reasons I won’t go into. And then, a black screen clears to reveal Nicole sitting in the front of her car, with a piece of pipe taped through the window. And you have to turn the engine on, and then either turn it off again, or sit in the fumes until Nicole dies! Seems like Rachel is the only one who didn’t commit suicide after all, jazz hands! The content warning at the start is necessary, then. But not because the game discusses sucide frankly or sensitively or in a meaningful way, but because you can actually do it. The scene isn’t even earned through what the game does up until that moment. It just happens. I don’t even know how to end this review now. I kind of want to just present those facts at the end, and then point vehemently at them. Which is basically what happens in The Suicide Of Rachel Foster, I suppose. In which case, reading this review is a pretty good replica of the experience of playing.