That was also the experience of developer Blackbird Interactive as it began to develop Shipbreaker and brought it to Early Access. The theme quickly crystallised, but figuring out how freeform cutting would actually work was a lot harder, setting stern technical challenges that were never really solved, posing questions about player freedom that resulted in surprising answers, and causing spaceship designers’ nightmares.

Shipbreaker emerged from a studio game jam project produced after the completion of (the excellent) 2016 RTS Homeworld: Deserts of Kharak. “It was a great way to get people to create a bloodletting, clear the air from the game we’d just shipped and get people re-invigorated,” associate creative director Elliott Hudson tells me. Called Hello Collector, the game was about grappling and clambering around procedurally generated asteroids in zero-G and firstperson, trying to find loot. “We were trying to recreate that feeling from the movie Gravity where Sandra Bullock is tumbling through space debris and grabbing on to a cable and that’s the only thing keeping her from flying into the void and being lost forever.”

The concept was immediately snapped up for further development, during which it evolved into Shipbreaker. But even if back at that stage space was hard, there was no breaking of ships. Until, that is, a key inspiration came forward: the beach at Alang in Gujarat on the western coast of India. Here, giant cargo ships are driven onto its wide sand and broken down by hundreds of workers with blowtorches, many without protective gear as they send great slabs of hulls crashing to the ground, where they’re further chopped to pieces. “It’s incredibly dangerous, it’s this shadowy side of the ship industry,” says Hudson. “We’ve always been fascinated by it, and we had a little bit of it in Deserts of Kharak, but Shipbreaker was an opportunity to dive even deeper and it inspired some of its themes, of exploitation and the bluecollar worker.” “So you have this big ship and you have to take it apart all by yourself,” adds game director Trey Smith. You are a shipbreaker, newly employed by a thoroughly exploitative corporation to take decommissioned starships of various sizes apart, reclaiming their parts to repay a vast personal debt.

It’s a simple-sounding concept, but its wide scope quickly became evident through a multitude of questions. “How small a piece can the player cut off at a time? How big can they go? That whole sense of scale has been tricky,” says Smith. First, though, there was the question of how the cutting would even work. Should the game give players total freedom to cut any shape they want? That’s the way a lot of cutting games do it, but the team found all sorts of problems with that kind of freedom. Most games with freeform cutting, as with Wolfenstein: The New Order’s laser cutter, only let you cut specific – often small – objects, and they tend to work by applying cuts to a preset grid. For a game that lets you cut anything on very large objects, that wouldn’t work. “We wanted players to be able to cut across the whole ship and for it not to feel gridified, like it was set up to do that,” says Hudson. “It wouldn’t play very well and would have also been too computationally expensive, anyway.”

So Shipbreaker takes the other route to cutting, which is all about scoring long, perfectly straight lines. But this has led to many problems since, because though you can cut wherever you want, it’s not truly freeform. “And that’s the expectation, the freeform thing. It’s what everyone wants.” Blackbird spent a long time trying to find a middle ground, using the slicing tech they’d developed to create freer cuts, but with the small team also having to solve many other problems besides, they couldn’t find one. “In a way, it’s unfortunate,” says Hudson. “But I think long-term, if that was the way you had to do it, I think it’d be too tedious. We were aware that freeform cutting might get too noodly for players to cut their way through an entire ship, and it would heavily limit the size of the ships. We certainly wouldn’t be able to go as large as we’re going if you had to do it all by hand like that.”

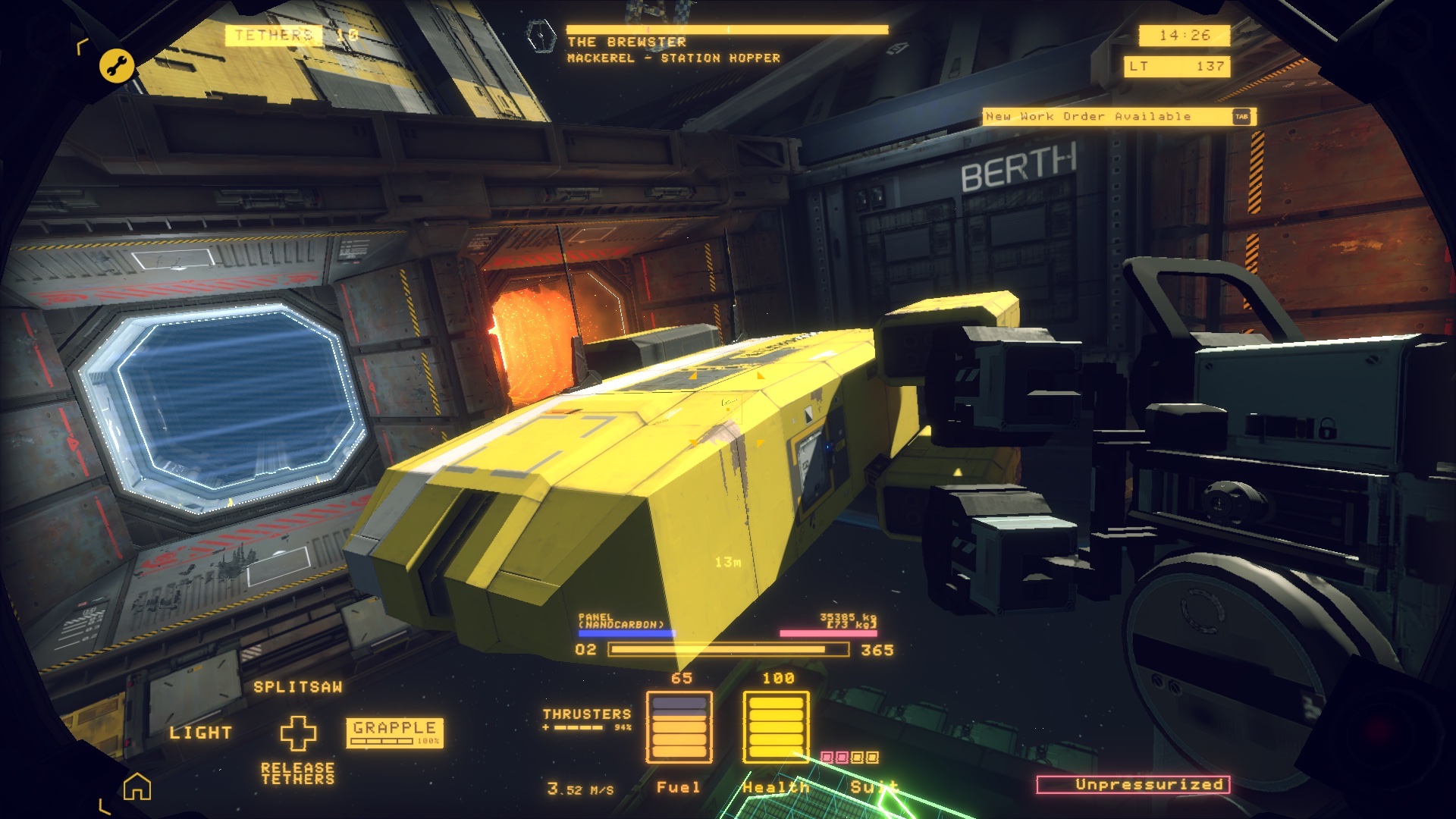

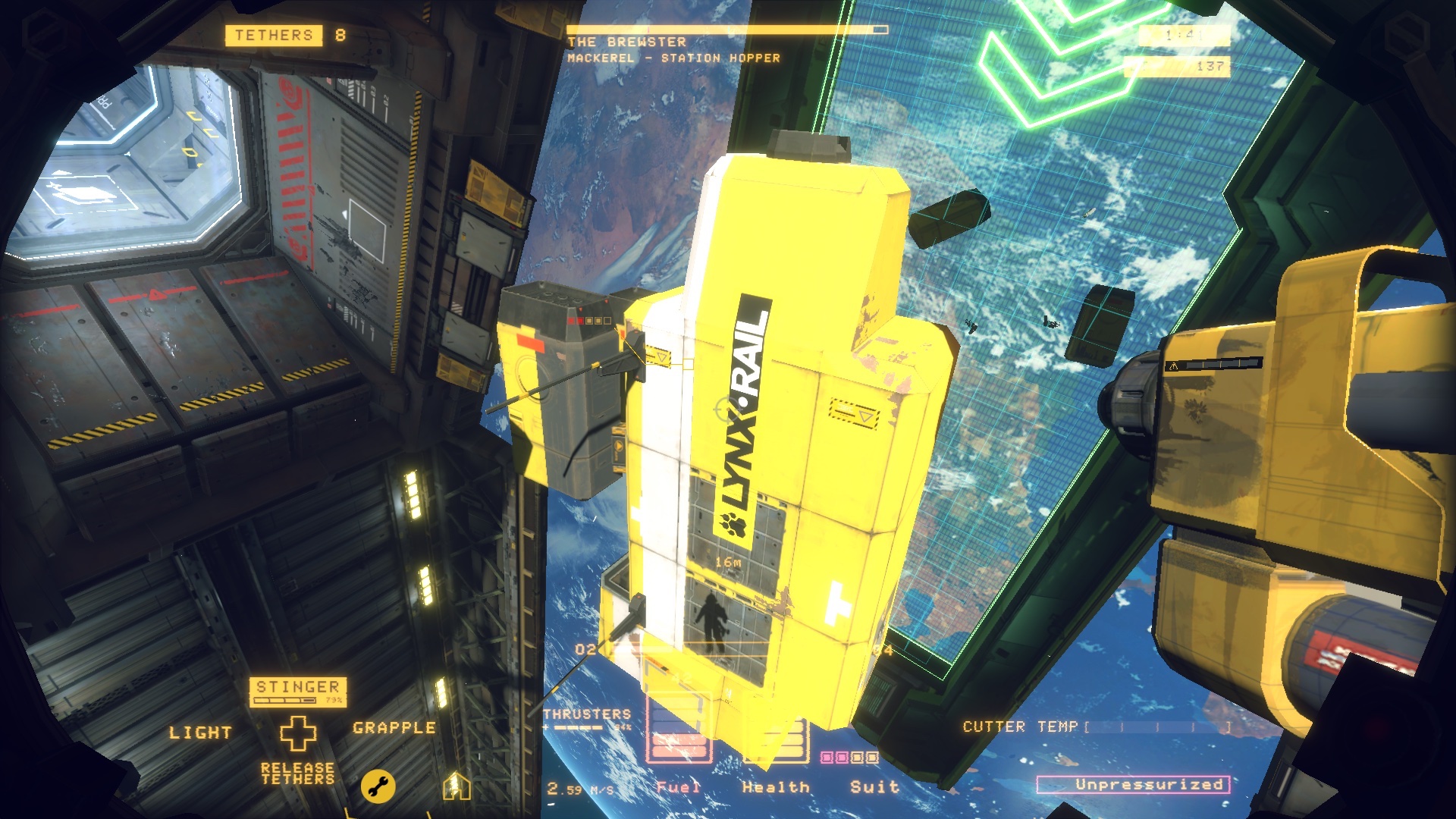

The tool that emerged from all this sweat was the Splitsaw. This heavy-duty industrial laser shoots two beams directly forward before dividing to sweep in opposite directions, cutting a long, straight line. A lot of work went into figuring out that visual representation. “We were trying to make the player feels it functions exactly how they think it’s going to, even before they fire it,” says Smith. “Yeah, that’s why two beams split in different directions, to better communicate to the player that it’s going to be doing a slice,” says Hudson. “We used to have one laser that would track in one direction.” “It felt super canny, like you were locked in until the animation was over.” The team also tried a tool that would send out a lateral shockwave effect – Hudson describes it as Street Fighter-like – that would slice things. “It worked, but it felt way too…” “Weapony,” says Smith. “Yeah, and less of a tool.” It was important that Shipbreaker’s equipment doesn’t feel like weaponry. It’s meant to be heavy industrial equipment, and you’re meant to be a worker, not a power-fantasy soldier. That principle extends to your other cutting tool, the Stinger, which shoots out a single beam. This tool was developed in response to the fact that players needed a tool with a little more precision. “With the splitsaw you almost always cut pipes behind the thing you want and blow everything up, so we needed something that lets players finesse things more.”

The Stinger came about at an important time in Shipbreaker’s development. By this point, the team had introduced pressurisation inside the hulls of the ships, so that if you made any hole in a hull before you depressurised the ship, it’d explode. Pressurisation created cool moments, and helped give structure to the process of shipbreaking, but explosions were far too frequent. So Hudson and art director Chris Williams got together to figure out a way of designing the ships to avoid them. The solution was to add a cavity between the outer hull and the pressurised interior, inside which the hull and interior are connected by yellow-chevroned joints. “The first time we were all sitting together in our little cinema doing a build review and Elliot sliced off all the connective tissue to one of the big hull panels, and it just went ‘thuhhhh’ and slowly drifted away…” says Smith. “Up to that point, you were just slicing and taking little squares and rectangles; that was the first time we saw we were making a shipbreaking game.”

The game was coming into focus: you’d be finding access and then squeezing into the cavity to find and cut each joint to release the outer hull. After all, though the game started out letting players cut through anything, the team realised that you shouldn’t be able to cut through the hull – at least with your early-game tools. “The issue was that it’s initially exciting for players to know they can cut through anything, but you quickly find it limits problem-solving and any sense of flow or directionality through the ship; you lose all meaning and choice,” says Hudson. “So, adding an exterior hull that you can’t cut but maintaining complete cut-ability of the interior allowed us to balance those two things.” By the end of the game, you can upgrade your tools enough to cut through anything (“that was important to us; technically, under the hood, everything is cuttable”). But that kind of freedom brings new problems to a veteran shipbreaker: it’s easy to make tiny – and explosive – nicks in things you really don’t mean to. The team is exploring ways of giving greater control – perhaps with a switch between high and low power – but the game already tries to show you what you’ll be cutting by drawing a dotted line in your reticle across the surface ahead of you, so you can adjust your aim and distance for precision.

But that cutting line was another challenging piece of design the team had to get into: what size chunks should players be aiming to cut? What made sense for the scale of the game? The answer they came to, four metres, will seem as abstract as the questions that posed it. But this scale is fundamental to the game as it is today, having transformed the way Shipbreaker’s ships are made. Originally, the ships were made much like objects in most other games: 40-metre meshes textured to look like they were made of many different panels and blocks. “Why not, right?” says Hudson. “But the way our cutting works, it’ll cut all 40 metres in one go. That’s how the game initially played and players were like, ‘Why is this happening? This is ridiculous.’”

So every ship has to be made from individual components fitted together, and most are built from four-metre panels, as if created with a giant Lego set. Some components go up to eight metres. “Beyond that, when players cut above eight metres, it feels ridiculous,” says Hudson. This new construction principle was, Hudson says, a nightmare for Shipbreaker’s artists, who suddenly found themselves trying to make out of Lego pieces spaceships that were meant to live up to visual director Brennan Massicotte’s beautiful Homeworld-esque concept art. For Smith, the team has steadily perfected that art as it produces new ships to bring the game toward final release. On the other hand, this standardised construction feels appropriate for Shipbreaker’s profoundly industrialised universe, bringing the whole project right back to that Indian beach, where giant rusting hulls are torn down on greasy sand. “If you go close to a cargo ship, you can see all the weld points for the panels and it is very standardised,” says Hudson. “Of course it is. It’s mass-scale production.”