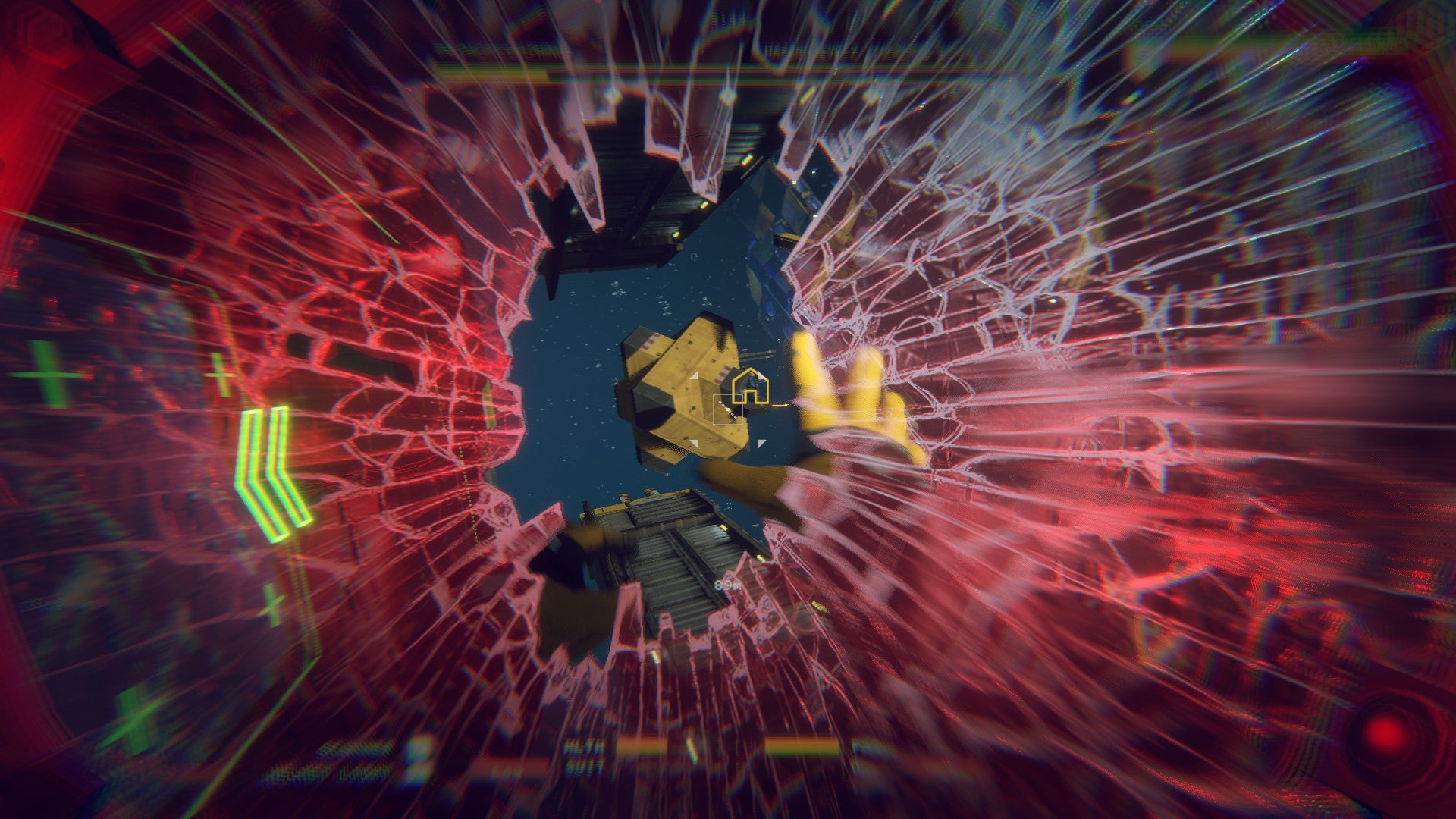

Going by Glassdoor reviews, Blackbird are doing a pretty solid job of not being Lynx. Blackbird recently adopted four-day working weeks, for instance, and strictly discourage overtime; Lynx force you to grind incessantly by billing you for everything from the dingy habitat that serves as mission hub to the oxygen you breathe on-shift. Blackbird have strong working class roots and plentiful experience of life at the “low end of the totem pole, dealing with decrees from corporate”, as game director Elliot Hudson describes his own time on the loading dock at one of Canada’s largest department stores. Previous employments range from paving streets and demolishing bridges to metal-working, dish-washing and farming. Lynx, by contrast, are a trillionaire tech dynasty whose executives might as well occupy a different dimension. But Blackbird are Lynx, of course, inasmuch as Blackbird are the real architect of Hardspace’s gratifying, but clownishly unsafe zero-G workplace simulation, which gives you 15 minutes to butcher space derelicts and grapple the pieces into hoppers without being incinerated, crushed, electrocuted or blasted into terminal orbit. Whether any aspect of that workplace is “a Blackbird or a Lynx thing” - in other words, how callously Blackbird decide to treat their player in service to a dystopian fiction - is a fascinating, open-ended question, especially now that the story has broached the topic of unionisation. Hardspace is an “international snapshot” of working class employment a few centuries from now, according to senior UX and game designer Vidhi Shah. Its art direction and soundtrack mix references to ‘blue collar’ labour in 1920s North America with ’labor work’ in present-day India, the chief visual inspiration being the Alang Ship Breaking Yard in Gujarat, where people carve up supertankers with blowtorches. The backstory, uncovered by decrypting data drives within the ships you dissect, details Lynx’s gradual overthrow of Earth’s old government and speaks to “the cyclical nature” of class struggle, as Hudson explains. “You see these industrial or technological advances throughout history, and they’re pushed by corporate interests, but they are operated by the working class who are sometimes exploited.” Hardspace can also be read as a commentary on the ‘playbour’ elements of contemporary service games, and by extension, the gamified elements of modern workplaces – habit-forming beeps and boops for rewards and penalties, progression bars and condescending ‘personalisation’ opportunities such as posters and stickers for your habitat and tools, all presented explicitly here as the mollifying tactics of an evil employer. There’s an unspoken invitation for players to ponder and perhaps, react against managerial systems and types of feedback which the game at once satirises and relies upon to keep you hooked. More immediately, Hardspace is designed to rebut the casually demeaning idea of manual labour as ‘unskilled’ next to, say, the brainy business of software development. As Shah says of the situation in India, “’labor work’ is almost always treated with much lower respect than ‘knowledge work,’ and never enjoys the same compensation or safety standards - physically or financially.” The game walks a tricky line between rebutting this snobbiness and over-romanticising physical graft. Starship butchery itself is spectacular, and has a palpable mastery curve: the more familiar you are with each class of vessel, the faster and more gracefully you’re able to strip out the choicest pieces, and there’s a fundamental delight to gauging the physics of objects of different densities. “There’s certain effects, there’s audio, there’s forces that get applied to the objects when you pull them apart - all those things are part of making that feel really satisfying,” Hudson comments. “[Because] hard manual labour can often be extremely satisfying. But that doesn’t take away from the fact that can also be extremely dangerous or dull over a long period of time.” The laser cutter and grappling tool you rent from Lynx are empowering toys, reminiscent both of Airfix models and Half-Life 2. Melt the yellow-chevroned joints along the spine of a science ship and you can lift away half the hull, as if peeling a banana. They’re also designed to feel worn-down and inadequate, however, needing regular repair and often requiring that you put yourself at risk to harvest the pick of a cruiser’s innards. The starting laser isn’t powerful enough to slash through dense thruster housing, for example, which means that you can’t switch off the fuel lines before disconnecting them from the core. Instead, you must zap the hoses and swoop down the resulting tunnel of flames to shut off the fuel before everything explodes. “This is an authoritarian company, they’re not really giving you the best technology, they’re not trying to make your life easier - the focus is the bottom line,” Shah says. Naturally, Lynx favour negative over positive incentives when it comes to assessing your progress. The player’s debt is visible everywhere from your save file to the kiosk where you’ll purchase jetpack fuel, and shift reports begin by listing all the components you’ve accidentally obliterated or thrown into the wrong hopper. “Lynx [are constantly] telling you how much you’ve destroyed, that’s always front and centre. Oh, you’ve destroyed not just a percentage of the ship, but a dollar value.” The menus themselves are deliberately unwieldy. “Sometimes we would not have iconography in the game, so the player now has to put in more work,” Shah says. “Even the smallest task can be quite labour-intensive. It’s very intentional - there’s not a lot of colour in the user interface, and it’s not slick, sometimes it’s an extra click that you have to go through.” One bemusing consequence of framing all these aggravations as “Lynx things” is that Blackbird’s on-going quality-of-line enhancements feel vaguely implausible, out of sync. The current Early Access version’s HUD is a huge improvement on the 2020 launch iteration – it’s much easier to monitor your oxygen, fuel and how much of each vessel is left to salvage. All the same, I was rubbing along handily enough with the old interface. From the perspective of a corner-cutting Lynx boss, it’s surely money gone to waste. I’m not the only one struggling to distinguish between the game and its fiction. Player feedback to Hardspace routinely blurs the line between views on Blackbird’s design decisions and views on working conditions at Lynx, with many users bringing in their own experiences of employment in transport or heavy industry. Open the Steam forums, and you’ll read truck drivers tutting about the lack of regulations for strapping down cargo, and former A&P mechanics likening the “Lynx token” upgrade system to the 19th century mining town practice of payment in company credit. You’ll also read polarized reactions to the main storyline, told through radio chatter and in-game emails, which charts efforts to found a shipbreaker’s union. The discussions here mirror discussions around unionisation in the wider games industry and community since GDC 2018. Again, the question “is this a Blackbird thing or a Lynx thing?” appears in how players fall into and out of character. When people complain about Lou, a garrulous union activist, it’s sometimes because they dislike being at preached by lefties or have had bad experiences with unions themselves, and sometimes because they resent the presence of unskippable background monologues in what was once a lightly narrated sandbox experience. (There’s a Free mode if you’d rather skip the story entirely.) “Unions are obviously a highly divisive political topic here in the west,” Hudson notes. “I think that’s maybe different in other parts of the world - in Europe, I understand it’s more commonplace, just a matter of business, but here [in North America], it’s highly divisive. And that goes back to the struggles of workers in the 40s and 50s, and how governments and corporations created pushback and propaganda about unions to build up this perception that they’re horrible and evil.” While its leanings are plain, Blackbird has tried to offer a “breadth of perspectives” on unions in the game. “You have several characters who aren’t in support of the union, and they have very good reasons for not being in support of the union.” The character who perhaps encompasses these divisions is Weaver - a former shipbreaker literally reborn as a manager after an accident during the cloning process, who serves as your tutor and supervisor. Weaver still loves the job, living it vicariously through his teams, which makes him reluctant to cause a fuss with upper management about things like the often-fatal absence of an automated ship decompression system, and tetchy about minor infractions such as shipbreakers making sneaky use of oxygen found aboard some ships, rather than buying Lynx-brand refills. He’s a caring presence, the voice in your ear talking you through each shift, but also, a company man. Designing Lynx, their technology and their management culture has been part of Blackbird’s own reinvention of themselves as a workplace during the game’s development. “I think the game exists because Blackbird already had a really good stance on the health and wellbeing of its employees,” Hudson says. There are lingering questions here, admittedly: the studio has yet to share the results of an investigation into former lead designer Jennifer Scheurle, who left in November 2021 after allegations of abusive behaviour during her career at other studios. “We wouldn’t even make a game like Shipbreaker if that wasn’t already part of the company’s DNA,” Hudson goes on. “But I think working on the game also reinforced back to us that yes, these are our values, and we need to walk the walk, right? We can’t just make a game about labour injustice and not make changes ourselves. So I think that has a really nice positive feedback loop, that has helped precipitate things like the change to a four day week, which has been phenomenal.” One odd thought I’m left with is whether the Hardspace playerbase is undergoing a similar process of self-invention, sparked by Blackbird’s elaborate blending of gamespace with workplace. The developer is stirring in the union storyline act by act, update by update; as with most Early Access games, this has given the studio the opportunity to monitor reactions and tweak things as appropriate, though Hudson doesn’t go into specifics. This dialogue between studio and player suggests that the unionisation theme could be productively, albeit riskily extended from the writing into the realm of community management. Gamers have an extensive history of “collective action” against developers, for better and worse: think of the petitions about Mass Effect 3’s original ending. Complaints that Hardspace forces you to participate in the union plotline, meanwhile, are a reminder that unions aren’t generally founded by bosses. So what if, rather than penning a story about shipbreakers organising against a villainous employer, Blackbird embraced Lynxhood and tried to provoke its audience into forming a union of their own?