“We felt really good,” product owner Paul Keslin tells me. But that feeling soon changed. The game was beset by crash bugs and complaints of repetitive play, and its Steam review scores tumbled. For its small development team, the reception was a shock – “Immediately, the feeling was not a good one”. The post-launch plan was thrown in the bin, and so began the long job of turning the game around in the eyes of its players. Now, nearly a year later, it’s paid off. Generation Zero’s recent Steam reviews have it sitting at Very Positive, descriptive of a game with an interesting and beautiful open world and broadly satisfying loot-shooting. I’ve been enjoying the journey on which it’s sending me through the Nordic countryside, and blowing up robots with pinpoint shots feels great. So how did its makers do it? And what is it like to see a game on which you’ve worked release to such a bad reception?

It’s often hard to understand how developers can be surprised about problems with their games. In the cold light of your own monitor, they can look so obvious. From the inside, though, when you’ve worked on the manifold elements that go into a single game, it’s difficult to see it in its entirety. So after Generation Zero’s large closed beta in October 2018, its makers felt good about what they’d produced as a small team inside Avalanche, working with a small budget on the studio’s first self-published new IP. “The feedback was overwhelmingly positive,” says Keslin. “We felt we had a pretty good handle on the information we had at hand and that we’d just roll from there. So launch was a bit of a disparity. I think our Steam score at the time was a 46. It was a bit like, ‘What happened?’” To be clear, the team were aware of things to iron out. They had a hotfix planned for the day of release, and another that would deal with a known crash-bug. They had a few developers standing by, ready to jump on any issues. But after Generation Zero’s first weekend, it was very clear that there was a lot more wrong than they’d accounted for. Some of it was technical, some was down to design. Some was more subtle. All of it needed addressing.

The first step was to collate reviews and look at the available data on player activity – the weapons being used, how long they were playing, the questlines they embarked on, where they were going. The team talked about their gut feelings on what was up. Keslin pulled in Avalanche’s management to get their insights on what to do next, and talked community management and PR about keeping communication open with the public. And from this process emerged a picture of the problems they faced, and a plan to deal with them. “The intent was to stem the bleeding as fast as possible, if we want to use that phrase, because it wasn’t a great start,” says Keslin. “We knew the game was better than this, fans were even saying in some of the comments, ‘It would be a great game, but…’”

It was a process of triage, and the most pressing problem was that players were having problems completing missions. Your journey through Generation Zero’s robo-infested Sweden is governed by quests which generally have you visiting specific locations, finding objects and destroying certain enemies, and if you did them in orders that the team hadn’t considered they could get stuck, preventing progression. Sometimes they’d get so stuck that even new saves would be affected. “It came as a nasty surprise for us,” says Keslin. “The last thing we want to do is release a game that people would point to as bad. Looking back at it, a lot of the issues that popped up were related to us having a small development team and limited resources. Given this setup, we were unable to check all of the potential permutations that manifest themselves in an open-world game.” A second major problem was a general criticism that the game didn’t seem to offer enough to do, offering repetitive houses and buildings to loot for supplies and few different enemies to fight. “We saw a lot of people not getting through the first couple of hours, because they thought it was samey,” says Keslin. “There was more variety after you got out of the first couple of hours, but a lot of people got stuck.” So fixes tried to raise the level of variety in the first areas and to hint to players that they could expect more later, along with more tutorialising pop-ups to ensure that no one was missing out on what they could already do.

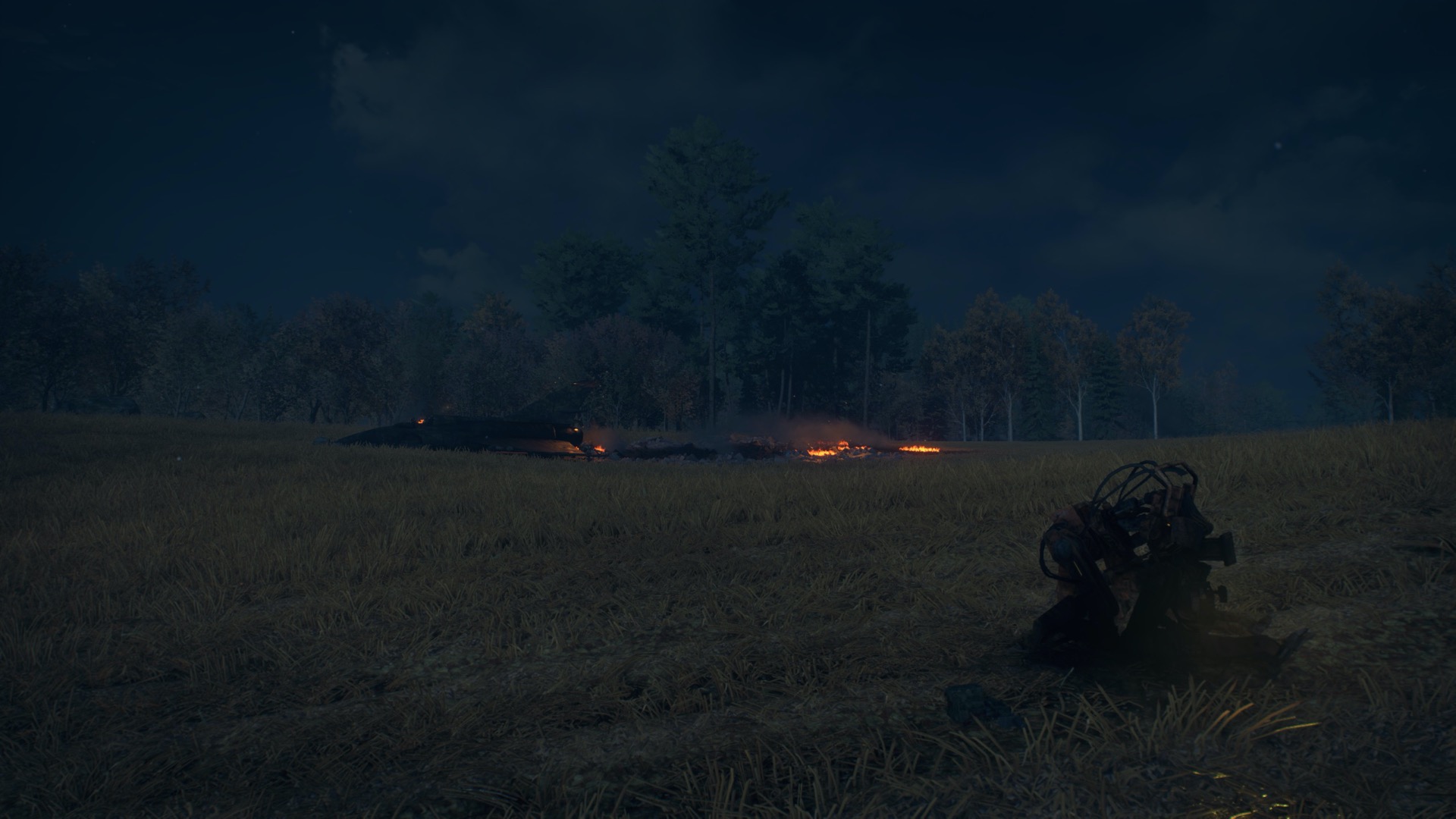

And there was a softer, more subtle issue, one which related to Generation Zero’s very nature. “There could have been a mismatch between what we were going for and what players expected,” says Keslin. In short, the problem was that Generation Zero wasn’t meant to be an action game. The whole project was inspired by Avalanche’s theHunter: Call of the Wild, a hunting sim in which you creep through beautiful forests, attempting not to spook deer so you can watch them (clearly, shooting the deer is not the right way to play). Generation Zero’s creative director, Emil Krafting, wanted to make a game that flipped theHunter’s concept on its head: “What if you’re the one being hunted?” It would be slow, quiet, stealth-driven, atmospheric. And to draw you through the world, you’d be finding fragments of documents and scenographic tableaus that explain what’s up with all them robos. “We wanted people to explore, take their time, feel immersed in the game world,” says Keslin. “A critique could be made that we made it a bit too true to life, where if you’re going to wander the countryside there might not be something to get excited about every five feet.”

After all, when you give a player a gun and robots to shoot, and they kind of expect to run around and attack everything in sight. “Expectations could have been out of whack, and some of that’s on us, right?” says Keslin. Resetting player expectations is a hard problem for any game. Generation Zero hoped to slow players down by restricting ammo supplies to naturally encourage them place shots with care and sometimes avoid combat, and to provide an abundance of support items – radios and flares which distract the robots – to suggest less direct playstyles. But Keslin, who describes himself as a shotgun player who just wants to blast things in the face, knows that players want to do it their way. “Setting the atmosphere only does so much.” And something that became evident was that some players had made assumptions about what kind of game it was from its screenshots and trailers, which showed off an apparently big-budget game with lots of action, made by a studio with a reputation for action.

“As much as we’d talk about being a small team with a small budget, people are sitting there saying, ‘Your screenshots look amazing!’ So that pulled in more people, because they’re excited by something that looks like AAA games.” So another thing the team focused on was the way the game is described and shown off, so better communicates its essential nature. The screenshots still look pretty and there’s plenty of gunplay – such is the reality of maintaining immediate appeal – but there’s a greater sense of quieter scene-setting. As June arrived, a little over two months after release, Keslin says the team was hitting its stride. Many bugs had been fixed, and bikes were added to the game. “If people were saying the world is very open and big, and they were concerned about not having enough things in it, then OK, here was one way to travel a bit faster.” And that was when, Keslin says, players started to invest more hope in the game. Not only was it being fixed, but they could also trust the team to add more to it: this was a going concern.

In August, the game took a bigger swing into the positive. Along with rare weapon drops, the team added a new feature, Rivals. Sometimes when players die to a robot, or when a player kills enough machines in an area, a robot will be given a unique designator and some extra strength, lending the game more variety and a greater sense that it’s responding to player action. Then, in November, the team added Alpine Unrest, paid DLC which added a whole new area to the game. “Think of it as a microcosm of what we wanted to do, a bit of our response to feedback and a bit of what we wanted to add.” It features NPCs, which offer more overt storytelling in addition to the usual papertrail of letters, diaries and documents, and its world is more densely populated with detail. Keslin was quite aware that some players would question the release of paid DLC when they felt the core game still had issues. “As a student of the industry, I always expect that players are going to say that.” Kelsin is an EA veteran, after all. “So do I still feel confident in what we’re doing? For me, the answer was yes. At that point, we’d fixed the majority of the launch issues, and we’re on our way to addressing some of the softer issues that were there. It was a chunky experience and we felt it was a fair cost for players, and it wasn’t like we’d stopped with our free updates.”

Alpine Unrest raised the team’s energy levels. They’d long passed the dark times of the launch, and the rising Steam review score and metrics which Keslin says peg average playtimes in the double digits were proof that they’d genuinely turned the game around. And work continues. The team can’t get complacent, and the task of interpreting feedback and sculpting the game so it stays true to its nature while satisfying expectations is essentially never-ending. As we finish our interview, I noticed a recent review from a player with 334 hours in-game. It complains that nothing works properly, and slaps on it a Not Recommended. Keslin laughs and claps his hands, a reaction I suspect he couldn’t have made a year ago. “Those are the best ones! Oh boy.”